Michel de Montaigne (1533-1595) en Spinoza?

In de komende VHS Spinozaweek staat voor dinsdagavond 24 juli geprogrammeerd: “René Willemsen: Montaigne (en Spinoza).” Opvallend dat Spinoza tussen haakjes staat. Het kan betekenen dat er veel over Montaigne en weinig over Spinoza zal worden gesproken. Het kan ook betekenen dat er niets bekend is over de vraag of Spinoza iets van Montaigne heeft gelezen (in z'n bibliotheek had hij niets) – en of Montaigne hem eigenlijk wel bekend was. Onbekendheid lijkt onwaarschijnlijk daar zijn goede bekende en wellicht vriend Jan Hendrik Glazemaker Montaigne vertaalde: Alle de werken van de Heer Michel de Montagne ... Bestaande in zyn proeven ... uijt de Fransche in de Nederlantsche taal vertaalt door J.H. Glazemaker, Amsterdam: Willem van Lamsvelt, 1672

In de komende VHS Spinozaweek staat voor dinsdagavond 24 juli geprogrammeerd: “René Willemsen: Montaigne (en Spinoza).” Opvallend dat Spinoza tussen haakjes staat. Het kan betekenen dat er veel over Montaigne en weinig over Spinoza zal worden gesproken. Het kan ook betekenen dat er niets bekend is over de vraag of Spinoza iets van Montaigne heeft gelezen (in z'n bibliotheek had hij niets) – en of Montaigne hem eigenlijk wel bekend was. Onbekendheid lijkt onwaarschijnlijk daar zijn goede bekende en wellicht vriend Jan Hendrik Glazemaker Montaigne vertaalde: Alle de werken van de Heer Michel de Montagne ... Bestaande in zyn proeven ... uijt de Fransche in de Nederlantsche taal vertaalt door J.H. Glazemaker, Amsterdam: Willem van Lamsvelt, 1672

Een groter contrast tussen twee filosofen is nauwelijks denkbaar: waar Spinoza zichzelf zoveel mogelijk buiten beeld wilde houden, was Montaigne, de uitvinder van het persoonlijke essay, een filosoof die zichzelf en zijn eigen leven in het middelpunt plaatste.

Michel Eyquem de Montaigne is vooral bekend geworden om zijn Essays. Hij werd door zijn vader opgevoed als humanist en leerde al vroeg Latijn, Grieks, Frans en Retorica. Hij was raadsheer in het parlement (gerechtshof) van Bordeaux, waarvan hij ook nog enige tijd burgemeester was. In de 13 jaar van zijn raadsheerschap werd hij geconfronteerd met de irrationele praktijken van vervolging van aanhangers van de reformatie, martelingen als bron van bewijs en heksenvervolgingen en -verbrandingen. Op zijn zevenendertigste kon hij die vorm van rechtspleging niet meer aanzien, en trok de edelman zich terug op zijn kasteel in Zuid-Frankrijk om er naast het beheren van zijn landgoed zich te ontpoppen als wijsgeer die zijn overdenkingen wijdde aan het ‘leven op het platteland’, wat inhield: zich wijden aan reflectie en filosofie. Hij streefde naar het stoïcijnse ideaal van de standvastige man, die zich niet door emoties wilde laten overheersen en een levensstijl in de geest van Epicurus trachtte te leiden. Wat door zijn niersteenaanvallen nog niet zo eenvoudig was. Popkin zag in hem echter “the most significant figure in the sixteenth century revival of ancient scepticism.”

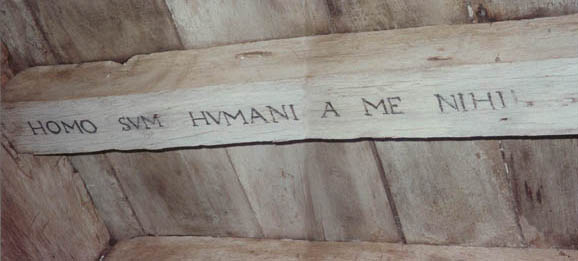

In dat kasteel had hij in een toren zijn bibliotheek ingericht. Op de balken van die bibliotheek liet hij spreuken aanbrengen van antieke auteurs die hem inspireerden. Het was immers te tijd van de renaissance, waarin het humanisme hoogtij vierde.

Zijn ‘onderzoek’ was vooral zelfonderzoek, waarvan hij de resultaten neerlegde in zijn essays - letterlijk ‘probeersels’. Hij was de eerste schrijver die dat zo deed, en daarmee is hij de eerste essayist. Zijn probeersels getuigen van een grote zelfrelativering, die ook door zijn tijdgenoten op waarde werd geschat.

In dit boek staan de bovenvermelde spreuken centraal. De auteur behandelt alle spreuken, hij geeft van het Latijn en het Grieks een vertaling en beschrijft de betekenis van de spreuken voor Montaigne zelf en de weerslag daarvan in zijn Essays. De titel Adagia werd eraan gegeven in navolging van Erasmus. [Van hier]

* * *

Ik vermoed dat dát de enige zinvolle manier is om beide denkers op elkaar te betrekken. Graag neem ik hier de interessante inleidende tekst van de website van de Univ. Utrecht over.

For instance, Giovanni Picco della Mirandola’s Oration on the Dignity of Man (1486) offers such a hierarchical conception of beings, that puts man in a position of supremacy in the world, characterizing him as a non-fixed entity, without any pre-determined role to play. In the seventeenth century, e.g. in Descartes’ philosophy, we also find such assessments of man’s superiority over nature and other beings in the world. Very different from these perspectives are Montaigne’s Essays and Spinoza’s works, where we find, on the contrary, tendencies to place man immanently within the boundaries of nature (which is conceived differently), and criticisms of the illusions which isolate man from the rest of nature. In spite of this effort to do away with the central place and role of man in nature, and also in philosophical discourse itself, man is still a central topic in Montaigne’s and Spinoza’s work.

Man thus conceived, viz. as dependent on nature, not auonomous but made up of passions and imaginations, is the object of philosophy in a way that opposes philosophy to theology. The field of man is the object and goal of Montaigne’s and Spinoza’s philosophies: they separate this topic from, nay oppose it to all theological discussions about God and Grace. But that does not mean that man is the theoretical starting point of the philosophical discourse. In both philosophies nature in motion is a stronger ontological basis for understanding men’s actions, passions and reflections.

Early modern philosophy

This talk will focus on the way these authors characterize man. He is no longer defined as a rational animal, nor do they conceive him as the union of thinking and extended substances (as Descartes does). On the contrary, the core of man is made up of passions and the imagination. This also means that man is constituted by movement and instability rather than by a static state and the capacity to act autonomously and independently.

It is not only fruitful to make a structural comparison between these two authors on these aspects, but we can also recast early modern philosophy as constituted as well by this philosophical trend, starting from Montaigne and reaching its fulfillment in Spinoza, through various historico-philosophical mediations, especially Hobbes and Descartes. [van hier]

___________

Michel de Montaigne in de Humanistische Canon (waarvandaan de foto van de balk geleend is)

Mooie vergelijking tussen (boeken over) Spinoza en Montaigne door Jessa Crispin: “Life Stories. Is it worth knowing about the lives philosophers led, or is their philosophy enough?” [hier]

Richard H. Popkin: The History of Scepticism from Erasmus to Spinoza (1979). Wijdde daarin een hoofdstuk aan Michel de Montaigne and the ‘Nouveaux Pyrrhonniens’ – en een hoofdstuk over Spinoza, maar geeft nergens een vergelijking tussen beide filosofen. [books.google]