Robinson Jeffers (1887-1962) 'radical Spinozaist', dichter

Amerikaans dichter en schrijver, geboren in Pittsburgh in Pennsylvania als zoon van een presbyteriaans dominee en professor in de oudtestamentische literatuur. Hij studeerde aan verschillende universiteiten in Amerika, Zwitserland en Duitsland, o.a. medicijnen en Engelse literatuur. 1

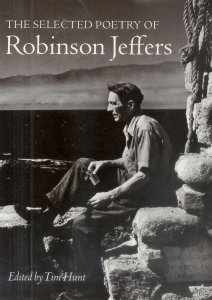

Op Whalt Whitman-achtige wijze, zo lees ik bij Christopher John MacGowan 2, articuleerde hij zijn thema van de uiteindelijke zinloosheid van het menselijk leven tegenover de kracht van de natuur en van de corruptie van de uiteindelijk gedoemde beschaving. Hij schreef zijn gedichten, vanaf 1924 bijna als kluizenaar levend aan de rand van de Stille Oceaan vlakbij Carmel in Californië in een natuurstenen  huis en toren die hij eigenhandig bouwde: "Tor House and Hawk Tower". Hij werd bekend om z’n verhalende gedichten en nogal mythische/mystieke lyriek. Hij zag de mens vooral als nietig wezen in de grote onpersoonlijke kosmos. Z’n favoriete dier was de havik, waarover hij meermalen dichtte. Hij anticipeerde de wat later genoemd werd, ‘eco-poetry’.

huis en toren die hij eigenhandig bouwde: "Tor House and Hawk Tower". Hij werd bekend om z’n verhalende gedichten en nogal mythische/mystieke lyriek. Hij zag de mens vooral als nietig wezen in de grote onpersoonlijke kosmos. Z’n favoriete dier was de havik, waarover hij meermalen dichtte. Hij anticipeerde de wat later genoemd werd, ‘eco-poetry’.

In z’n latere gedicht Carmel Point schreef hij:

We must uncenter our minds from ourselves;We must unhumanize our views a little, and become confident

As the rock and ocean that we were made from.

Of hij Spinoza bestudeerd heeft, weet ik niet, maar hij zou wel geschreven hebben: “it is our privilege and felicity to love God for his beauty, without claiming or expecting love from him” and to conclude from that that “we are not important to [God], but he to us.” Ik neem zijn Spinoza-studie dus aan. 3

De associatie van Jeffers met Spinoza is kennelijk zo gek nog niet. George Sessions’ artikel ken ik niet, maar hij schreef: Spinoza and Jeffers on man in nature. 4 Hoe verder ik doorzoek, hoe meer daarvan blijkt. Bill Deval noteert in “The Deep Ecology Movement”, waarbij hij verwijst naar deze Sessions en anderen: “It has be claimed by several writers that the poet-philosopher Robinson Jeffers, who lived most of his life on the California coastline at Big Sur, was Spinoza's twentieth century "evangelist" and that Jeffers gave Spinoza's philosophy an explicitly ecological interpretation." 5

Luc Ferry noemt in “The new ecological order” 6 verwijzend naar deze Sessions, Jeffers zelfs een ‘radical Spinozaist’

Michael Levine schrijft in het Lemma Pantheism in de Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy:

“Robinson Jeffers suggests that what may be important to the pantheist, and regarded as "a kind of salvation," is neither the realisation of the theist's hope for personal immortality, nor the atheists' (or theists') desire to be remembered in certain ways — although the pantheist can desire this as well. Instead, what is distinctively significant is the recognition of the individual as a part of the Unity — what Jeffers calls the "one organic whole … this one God." The "parts change and pass, or die, people and races and rocks and stars," but the whole remains. He says, "… all its parts are different expressions of the same energy, and they are all in communication with each other, influencing each other, [and are] therefore parts of one organic whole." (See, George Sessions 1977: 481-528). Part of what Jeffers is suggesting is that "salvation" (or immortality) it is not so much a matter of the fact of one's survival in some form; rather, "salvation" consists in the recognition of the "oneness" or Unity of everything. "[T]his whole alone is worthy of the deeper sort of love; and that there is peace, freedom, I might say a kind of salvation, in turning one's affections outward toward this one God, rather than inwards on one's self, or on humanity." This is impersonal rather than personal immortality or salvation, but it is different from the kinds of impersonal survival discussed above. It may even be regarded as a kind of personal salvation, since Jeffers suggests that salvation can be experienced for oneself while alive — and only when alive. Such salvation resembles neither impersonal forms of immortality, nor theists' personal life after death. 7

En Warwick Fox: “For Jeffers, 'This whole is in all its parts so beautiful, and is felt by me to be so intensely in earnest, that I am compelled to love it.' Although Jeffers may represent a relatively extreme exemplar of cosmologically based identification, it should nevertheless be clear that this form of identification issues at least--perhaps even primarily?--in an orientation of steadfast (as opposed to fair-weather) friendliness.” 8

Kortom, genoeg achtergrond, dunkt me, om één van zijn bekendste gedichten, Rock and Hawk, spinozaïsch te duiden.

| Rock and Hawk

Here is a symbol in which On the headland, where the seawind Lets no tree grow,

Earthquake-proved, and signatured To hang in the future sky; Not the cross, not the hive,

But this; bright power, dark peace;

Life with calm death; the falcon's Which failure cannot cast down Nor success make proud. Robinson Jeffers |

Rots en Havik Hier is een symbool waarinVele hoge tragische gedachten Letten op hun eigen ogen.

Deze grijze rots, hoog staand Door tijden van stormen: op z’n top Is een valk neergestreken.

Hier, denk ik, is uw embleem Woest bewustzijn samen met definitieve ongeïnteresseerdheid;

Leven met kalme dood, des valks Welks falen niet terneerslaan Noch succes trots kan maken. Robinson Jeffers

|

Hoor hier op een video, die iemand twee maanden geleden op YouTube plaatste, Robinson Jeffers zijn gedicht Wise men in their bad hours lezen

Wise men in their bad hours

Wise men in their bad hours have envied

The little people making merry like grasshoppers

In spots of sunlight, hardly thinking

Backward but never forward, and if they somehow

Take hold upon the future they do it

Half asleep, with the tools of generation

Foolishly reduplicating

Folly in thirty-year periods; the eat and laugh too,

Groan against labors, wars and partings,

Dance, talk, dress and undress; wise men have pretended

The summer insects enviable;

One must indulge the wise in moments of mockery.

Strength and desire possess the future,

The breed of the grasshopper shrills, "What does the future

Matter, we shall be dead?" Ah, grasshoppers,

Death's a fierce meadowlark: but to die having made

Something more equal to the centuries

Than muscle and bone, is mostly to shed weakness.

The mountains are dead stone, the people

Admire or hate their stature, their insolent quietness,

The mountains are not softened nor troubled

And a few dead men's thoughts have the same temper.

Noten

1) Wikipedia

2) Christopher John MacGowan: Twentieth-century American poetry. Wiley-Blackwell, 2004, 331 pagina's - Over Robinson Jeffers P 58 – 59 zie books.google.nl3) Zo lees ik bij de unitaristische dominee over wie ik vorige week een blog had.

4) George Sessions: Spinoza and Jeffers on man in nature. In Inquiry: An Interdisciplinary Journal of Philosophy, 1502-3923, Volume 20, Issue 1, 1977, Pages 481 – 528]5)In: Robert C. Scharff & Val Dusek (Eds.) Philosophy of technology: the technological condition: an anthology; Wiley-Blackwell, 2003, 686 pagina's, p. 474 zie books.google.nl

6) Luc Ferry: The new ecological order. University of Chicago Press, 1995, 159 pagina's, p. 70 zie books.google.nl

7) Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy

8) Warwick Fox Toward a Transpersonal Ecologyzie verder:

Encyclopedia of Religion and Nature (PDF)

Christopher John MacGowan: Twentieth-century American poetry. Wiley-Blackwell, 2004, 331 pagina's - over Robinson Jeffers p 58 – 59 books.google.nl

website zeiler Tom Zijlstra

____________________

Aanvulling 1 februari 2015

Blogpost van S.C. Hickman, "Robinson Jeffers: The Poet Of Inhumanism," dat vooral over de vergelijking van Jeffers met Spinoza gaat. "Biographer Arthur Coffin referred to Benedict Spinoza, the famous philosopher, calling Jeffers “Spinoza’s twentieth century evangelist.”