Volgens Schleiermacher had Novalis dezelfde opvallende positie in de kunst als Spinoza in de wetenschap

Het werk waarmee hij beroemd werd, Über die Religion. Reden an die Gebildeten

unter ihren Verächtern, publiceerde Friedrich

Schleiermacher (1768 - 1834) toen hij dertig jaar was in 1799 eerst nog anoniem.

Het werk had een enigszins Spinozistische strekking, maar slechts éénmaal komt

de naam van Spinoza erin voor en wel in de tweede rede "Über das Wesen der

Religion". Daarin komen de beroemde woorden voor [de eerste druk staat te

lezen bij zeno.org]

Het werk waarmee hij beroemd werd, Über die Religion. Reden an die Gebildeten

unter ihren Verächtern, publiceerde Friedrich

Schleiermacher (1768 - 1834) toen hij dertig jaar was in 1799 eerst nog anoniem.

Het werk had een enigszins Spinozistische strekking, maar slechts éénmaal komt

de naam van Spinoza erin voor en wel in de tweede rede "Über das Wesen der

Religion". Daarin komen de beroemde woorden voor [de eerste druk staat te

lezen bij zeno.org]

"Opfert mit mir ehrerbietig eine

Locke den Manen des heiligen verstoßenen Spinoza! Ihn durchdrang der hohe

Weltgeist, das Unendliche war sein Anfang und Ende, das Universum seine einzige

und ewige Liebe, in heiliger Unschuld und tiefer Demut spiegelte er sich in der

ewigen Welt, und sah zu wie auch Er ihr liebenswürdigster Spiegel war; voller

Religion war Er und voll heiligen Geistes; und darum steht Er auch da, allein

und unerreicht, Meister in seiner Kunst, aber erhaben über die profane Zunft,

ohne Jünger und ohne Bürgerrecht."

[Zie over de vertaling van “eine Locke den Manen” dit blog.]

In de tweede editie van 1806 die hier en daar flink werd herzien, waardoor de geur van Spinozisme enigszins afgezwakt werd - de term ‘Anschauung’ verving hij dikwijls door de term ‘Gefuhl’ - kwam de naam van Spinoza tweemaal voor, want aan de boven geciteerde passage voegde hij de volgende toe:

Warum soll ich Euch erst zeigen,

wie dasselbe gilt auch von der Kunst? wie Ihr auch her tausend Schatten und

Blendwerke und Irrthümer habt aus derselben Ursache? Nur schweigend, denn der

neue und tiefe Schmerz hat keine Worte, will ich Euch statt alles andern

hinweisen auf ein herrliches Beispiel, das Ihr alle kennen solltet eben so gut

als jenes, auf den zu früh entschlafenen göttlichen Jüngling, dem Alles Kunst

ward, was sein Geist berührte, seine ganze Weltbetrachtung unmittelbar zu Einem

großen Gedicht, den Ihr, wiewol er kaum mehr als die erten Laute wirklich

ausgesprochen hat, den reichsten Dihttern beigesellen müßt, den [jenen]

seltenen, die eben so tiefsinnig sind als klar und lebendig. An ihm schauet die

Kraft ber Begeisterung und der Besonnenheit eines frommen Gemüths, und bekennt

wenn die Philosophen werden religiös sein unb Gott suchen wie Spinoza und die Künstler

fromm sein und Chistum lieben wie Novalis, dann wird die große Auferstehung

gefeiert werden für beide Welten.

Hier werden Spinoza en Novalis naast elkaar geplaatst.

Aan de derde editie die 1821 verscheen, voegde Schleiermacher aantekeningen toe om toelichting te geven. Bij deze laatste passage verscheen de volgende aantekening die ik (gemakshalve*) geef in de Engelse vertaling door John Oman die in 1898 verscheen als On religion: speeches to its cultured despisers [cf. archive.org].**) Een toelichting die nog eens achtmaal de naam van Spinoza bevatte…

This passage on the departed

Novalis was first inserted in the second edition. Many I believe will wonder at

this juxtaposition, not seeing that he is like Spinoza, or that he holds the

same conspicuous position in art as Spinoza in science. Without destroying the

balance of the Speech, I could only suggest my reason. There is now another

reason why I should say no more. During these fifteen years the attention to

Spinoza, awakened by Jacobi's writings and continued by many later influences, which

was then somewhat marked, has relaxed. Novalis also has again become unknown to

many. At that time, however, these examples seemed significant and important.

Many coquetted in insipid poetry with religion, believing they were akin to the

profound Novalis, just as there were advocates enough of the All in the One

taken for followers of Spinoza who were equally distant from their original.

Novalis was cried down as an enthusiastic mystic by the prosaic, and Spinoza as

godless by the literalists. It was incumbent upon me to protest against this

view of Spinoza, seeing I would review the whole sphere of piety. Something

essential would have been wanting in the exposition of my views if I had not in

some way said that the mind and heart of this great man seemed deeply

influenced by piety, even though it were not Christian piety. The result might

have been different, had not the Christianity of that time been so distorted

and obscured by dry formulas and vain subtilties that the divine form could not

be expected to win the regard of a stranger. This I said in the first edition,

somewhat youthfully indeed, yet so that I have found nothing now needing to be

altered, for there was no reason to believe that I ascribed the Holy Spirit to

Spinoza in the special Christian sense of the word. As interpolation instead of

interpretation was not then so common or so honourable as at present, I

believed that a part of my work was well done. How was I to expect that,

because I ascribed piety to Spinoza, I would myself be taken for a Spinozist?

Yet I had never defended his system, and anything philosophic that was in my

book was manifestly inconsistent with the characteristics of his views and had

quite a different basis than the unity of substance. Even Jacobi has in his

criticism by no means hit upon what is most characteristic. When I recovered my

astonishment, in revising the second edition, this parallel occurred to me. As

it was known that Novalis in some points had a tendency to Catholicism, I felt

sure that, in praising his art, I should have his religious aberrations

ascribed me as Spinozism had been because I praised Spinoza's piety. Whether my

expectation has deceived me I do not yet very well know.

This passage on the departed

Novalis was first inserted in the second edition. Many I believe will wonder at

this juxtaposition, not seeing that he is like Spinoza, or that he holds the

same conspicuous position in art as Spinoza in science. Without destroying the

balance of the Speech, I could only suggest my reason. There is now another

reason why I should say no more. During these fifteen years the attention to

Spinoza, awakened by Jacobi's writings and continued by many later influences, which

was then somewhat marked, has relaxed. Novalis also has again become unknown to

many. At that time, however, these examples seemed significant and important.

Many coquetted in insipid poetry with religion, believing they were akin to the

profound Novalis, just as there were advocates enough of the All in the One

taken for followers of Spinoza who were equally distant from their original.

Novalis was cried down as an enthusiastic mystic by the prosaic, and Spinoza as

godless by the literalists. It was incumbent upon me to protest against this

view of Spinoza, seeing I would review the whole sphere of piety. Something

essential would have been wanting in the exposition of my views if I had not in

some way said that the mind and heart of this great man seemed deeply

influenced by piety, even though it were not Christian piety. The result might

have been different, had not the Christianity of that time been so distorted

and obscured by dry formulas and vain subtilties that the divine form could not

be expected to win the regard of a stranger. This I said in the first edition,

somewhat youthfully indeed, yet so that I have found nothing now needing to be

altered, for there was no reason to believe that I ascribed the Holy Spirit to

Spinoza in the special Christian sense of the word. As interpolation instead of

interpretation was not then so common or so honourable as at present, I

believed that a part of my work was well done. How was I to expect that,

because I ascribed piety to Spinoza, I would myself be taken for a Spinozist?

Yet I had never defended his system, and anything philosophic that was in my

book was manifestly inconsistent with the characteristics of his views and had

quite a different basis than the unity of substance. Even Jacobi has in his

criticism by no means hit upon what is most characteristic. When I recovered my

astonishment, in revising the second edition, this parallel occurred to me. As

it was known that Novalis in some points had a tendency to Catholicism, I felt

sure that, in praising his art, I should have his religious aberrations

ascribed me as Spinozism had been because I praised Spinoza's piety. Whether my

expectation has deceived me I do not yet very well know.

_______________

*) De kritische Pünjer-uitgave van 1879, die de tekst van de eerste editie gaf met de wijzigingen van de volgende edities in voetnoten (met II en III) die op archive.org staat, is in Gotisch schrift. De aangehaalde tekst uit de tweede editie heb ik daaruit gehaald en omgezet naar modern schrift - wat best veel werk is.

**) Uit Omans inleiding: “He [Schleiermacher] had long and earnestly been studying Spinoza, and acknowledged a large debt to him. Yet the Spinozism of Schleiermacher is more in form than substance. In his conception of the Universe Spinoza's distinction between natures naturans and natura naturata re-appears, natura naturans being the World-Spirit. We also find his doctrine of the immanence of the Infinite in the finite, and his distinction between things in their observed relations, and things as seen sub specie aeternitatis. But to Spinoza the individual was merely a delusion of the imagination, a section arbitrarily cut out of the Universe, while the motive of all Schleiermacher's speculation was to find reality for the individual as a whole within a whole.” Aldus John Oman in zijn inleiding op zijn Engelse vertaling van Schleiermachers hoofdwerk; en zie hoe beïnvloed door de Hegeliaanse Spinoza-interpretatie de vertaler was.

______________

Afbeelding Schleiermacher van wikipedia.

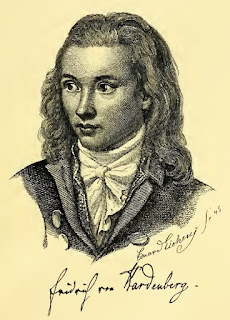

Afbeelding van Novalis (pseudoniem van Georg Friedrich Philipp Freiherr von Hardenberg) uit Meyers Lexikon Bücher in deutscher Sprache geschrieben, Sammlung von 21 Bänden zwischen 1905 und 1909 veröffentlicht.