Nog maar eens de vraag: was Spinoza de eerste zionist?

Een onderwerp waar al heel veel over geschreven is, maar

waar een boek dat speciaal gaat over zionisme en jodendom uiteraard niet om

heen kan, is de vraag: was Spinoza de eerste zionist? Dus heeft het boek van

Een onderwerp waar al heel veel over geschreven is, maar

waar een boek dat speciaal gaat over zionisme en jodendom uiteraard niet om

heen kan, is de vraag: was Spinoza de eerste zionist? Dus heeft het boek van

David Novak, Zionism and Judaism. A New Theory. Cambridge University Press, March 2015 – books.google

een heel hoofdstuk over deze vraag met – ik meld het maar even - de volgende paragrafen

2 Was Spinoza the First Zionist?

Ben-Gurion and Spinoza

Spinoza's Inversions of Classical Jewish Theology

The Proto-Zionist Statement

Spinoza's Old-New Judaism

Spinoza and the Zionist Dilemma

3 Secular Zionism: Political or Cultural?

David Novak, die aan politieke theologie doet en als verdediger fungeert van deelname vanuit het joodse geloof aan debatten en beslissingen over inrichting van de samenleving [cf. blog], heeft goed gezien dat bij het beantwoorden van die vraag ieder telkens een nieuwe Spinoza in elkaar knutselt. Hij doet dat weer op zijn manier. Om een indruk te geven hier een passage (aan de stijl proef je al in welke richting de auteur zal gaan):

Spinoza's Inversions of Classical Jewish Theology

Before we look at the one long sentence in Spinoza's Tractatus Theologico-Politicus that so impressed Ben-Gurion and other secular Zionists, we need to raise four questions. One, how radical was Spinoza's break from Judaism? Two, is what might be called Spinoza's "proto-Zionism" as radical a break from Judaism as Ben-Gurion seems to have thought it to be? In other words, how truly "secular" was Spinoza's "Zionism"? Three, does Spinoza have anything to offer the current dilemma of Zionists, namely, what would make Israel as a state of Jews (medinat yehudim) an authentically Jewish state (medinah yehudit), that is, a state that could be justified by appealing to at least some kind of Judaism? Could Spinoza be used to justify the existence of a Jewish state in the land of Israel theologically? (Like it or not, as we shall seen, Judaism is inextricably theological because the "God-question" is ubiquitous therein.) Four, does Spinoza's break from conventional Jewish theology make any "theological" reading of him self-contradictory, or does Spinoza have his own theology, which has at least some correspondence with Jewish tradition? I submit that dealing with these four questions will enable us to see what for many might well be a new Spinoza, especially Spinoza as a new kind of Zionist.

How radical Spinoza's break with the Jewish past was is arguable, as we shall see. Yet he certainly broke with what seems to have been unanimous Jewish religious opinion in his own time. And, even though he could have hardly predicted the subsequent effects of his break in later Jewish history, those effects have been profound, so profound that they are now still operative in the life of the Jewish people — and perhaps in the whole Western world — now more than 350 years later.' [p. 26]

* * *

Spinoza was uiteraard volstrekt geen zionist: geen seculiere, geen politieke en geen culturele. Het idee dat hij dat wel zou zijn is het gevolg van een misvatting van wat Spinoza schreef aan het eind van het derde hoofdstuk van de TTP zegt (ik hoef die passage hier niet te herhalen). Het is een mislezing vanuit verlangen Spinoza alsnog voor het (seculiere) jodendom te ‘behouden’.

* * *

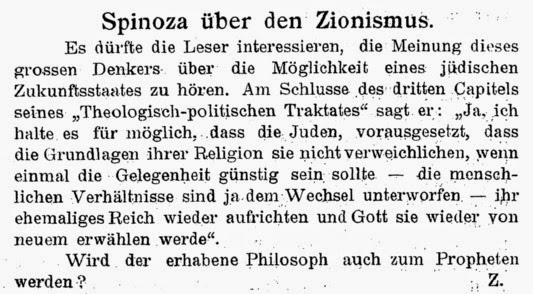

Ik vind het wel aardig hier een berichtje uit de joodse Duitse krant Die Welt van 1899, Heft 24 (16.6.1899) toe te voegen.