Samuel Hirszenberg (1865 – 1908) schilderde tweemaal Spinoza: als kind en als uitgestotene

Z’n twee Spinoza-schilderijen bracht ik al vijf jaar geleden (daarover onderaan dit blog méér) en z’n naam viel eerder in blogs, maar een eigen blog had ik nog niet aan hem gewijd. Het werd tijd. Tweemaal hield hij zich met een schilderij over Spinoza bezig: een vroeg werk in 1888 dat geïnspireerd zou zijn op werk van de Pools-joodse schilder Maurycy Gottlieb, werd het symbolische schilderij Uriel Acosta i Spinoza (Uriel d’Acosta en Spinoza als 7-jarig kind).

S. Hirszenberg "Uriel d'Acosta Instructing Young Spinoza" [van hier]

S. Hirszenberg "Uriel d'Acosta Instructing Young Spinoza" [van hier]

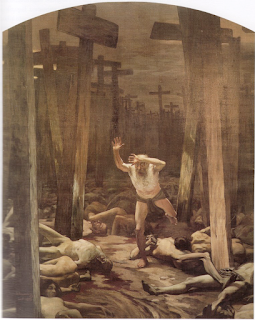

Een van z’n laatste werken ontstond in 1907, het jaar waarin hij naar Palestina trok, ik neem aan dat hij het nog in Polen maakte: Spinoza wyklêty (geëxcommuniceerde Spinoza). [Zie onder]

Tegen de zin van zijn vader, maar gesteund door een doktor kon hij als 15-jarige beginnen aan de Academie voor Beeldende Kunst in Kraków. Van 1885-1889 zette hij zijn studie voort aan de Akademie der Bildenden Künste München. In 1889 had hij een inzending bij de Kunstverein München, daarna toonde hij werk in Parijs waar hij een zilveren medaille won en waar hij aan de Académie Colarossi zijn opleiding voltooide. In 1891 keerde Hirszenberg naar Polen terug en in 1893 vestigde hij zich in zijn geboortestad Lodz.

Tegen de zin van zijn vader, maar gesteund door een doktor kon hij als 15-jarige beginnen aan de Academie voor Beeldende Kunst in Kraków. Van 1885-1889 zette hij zijn studie voort aan de Akademie der Bildenden Künste München. In 1889 had hij een inzending bij de Kunstverein München, daarna toonde hij werk in Parijs waar hij een zilveren medaille won en waar hij aan de Académie Colarossi zijn opleiding voltooide. In 1891 keerde Hirszenberg naar Polen terug en in 1893 vestigde hij zich in zijn geboortestad Lodz.

Ik citeer hetgeen Karl Schwartz in Jewish Artists of the 19th and 20th Centuries [Philosophical Library, New York, 1949] schreef over Samuel Hirszenberg.

“That the life of Samuel Hirszenberg came to an end just when his art began to take a decisive turn was a fateful loss. Hirszenberg came from Lodz. He studied in Cracow and Munich in the '80's, suffering great privation, and then lived in his hometown for seventeen years, where he painted a large number of pictures with Jewish content.

Nauczanie Talmudu, 1887 - School voor Talmudstudie

Sabbatnamiddag (1894)

On the whole his portrayals are pretty sentimental, as for instance the pictures “Jeshiba”; “A little piece of politics” and “Sabbath Afternoon”. These themes, recited in a leisurely narrative tone, are followed by several with an over-emphasized dramatic display: “The Jewish Cemetery” and “The Eternal Jew”.

On the whole his portrayals are pretty sentimental, as for instance the pictures “Jeshiba”; “A little piece of politics” and “Sabbath Afternoon”. These themes, recited in a leisurely narrative tone, are followed by several with an over-emphasized dramatic display: “The Jewish Cemetery” and “The Eternal Jew”.

After that, he acquired a more even style that found ultimate expression in the great monumental painting “Galuth”. Also called “They Wander”, it is composed of many figures, and not unjustly has won universal fame. With all its academic restraint, this picture surpasses by far his earlier works inasmuch as sentimentality has been corrected in favor of more spiritual content. Also, the picture has a certain significance as a first attempt to portray the vicissitude of Jewish life. With a minimum of pathos, the artist endeavors to treat the theme of Jewry that is condemned to perpetual wandering. Still, it remains “theme”, which means it is still too much of a literary narration. A procession of people moves soundlessly across an unending field of snow. A bent old man leads the procession, followed by men and women, young and old. One man carries the Torah, another carries a child in his arms, and a small girl has a bucket in her hand.

The picture is touching, but its pictorial value is not very great. Twenty-six years previously Gottlieb had painted his “Praying Jews”, likewise a monumental painting portraying God-fearing Jews. It would seem that he was the more talented of the two. The Galuth picture is the artist's last great work, for what follows are merely sketches.

Then Hirszenberg goes to Palestine. Out of the dismal grey of the Polish sky and the hopelessness of Jewish Galuth, he comes into the brilliant light of hopeful revival. With one stroke this experience changes the restraint in his soul, and his artistry. He has an urge to create new things, but realizes that he will require some time to get acclimated and to digest the new impressions. This is a new beginning altogether. He accumulates sketch after sketch and paints small designs. About a hundred are completed within a very short time one freer, lighter and more brilliant than the other. These little color studies herald the awakening of a newborn painter. Then, suddenly, an old ailment attacks him and within a few days deals him the death blow. There remain only the preparations that proclaim the progress of his art.By prematurely cutting off Hirszenberg's life, fate prevented one who began under the shadows of the past from becoming one of the truly great under the new conditions." [archive.org]

Spinoza wyklêty (Excommunicated Spinoza) of 1907, which shows the philosopher in seventeenth-century Dutch dress walking down the street and reading a book, while Orthodox members of the Jewish community withdraw from him in fear and anger. Hirszenberg directly experienced the confrontation between the old Jewish world and the new one explicitly addressed in these paintings. [Mirjam Rajner op YIVO] Dit is slechts een uitsnede uit het schilderij zoals gebruikt op de cover van Daniel B. Schwartz: The First Modern Jew: Spinoza and the History of an Image.

Een idee van het hele schilderij geeft deze kaart die je veel tegenkomt:

Alsmede deze illustratie, waarvan mij niet duidelijk is wie die heeft gemaakt. [o.a. hier te vinden]

Aanvulling 27 januari 2014, het hele schilderij in kleur [van hier groot]

Bronnen

Richard I. Cohen & Mirjam Rajner, "The Return of Wandering Jew(s) in Samuel Hirszenberg's Art" [hier]

Richard I. Cohen, Samuel Hirszenberg's imagination: An artist's interpretation of the Jewish dilemma at the fin-de-siècle. In: (Reprinted in Studia Judaica, 14 (2006), 87-114; Hebrew version in Image and Sound: Art, Music and History, ed. R.I. Cohen, Jerusalem, The Zalman Shazar Center, 2007, pp.327-353).